Join Friends of Burgess Park for LITTER PICK MONDAYS 8-9am

Meet in Chumleigh Gardens.

Litter pickers and gloves supplied.

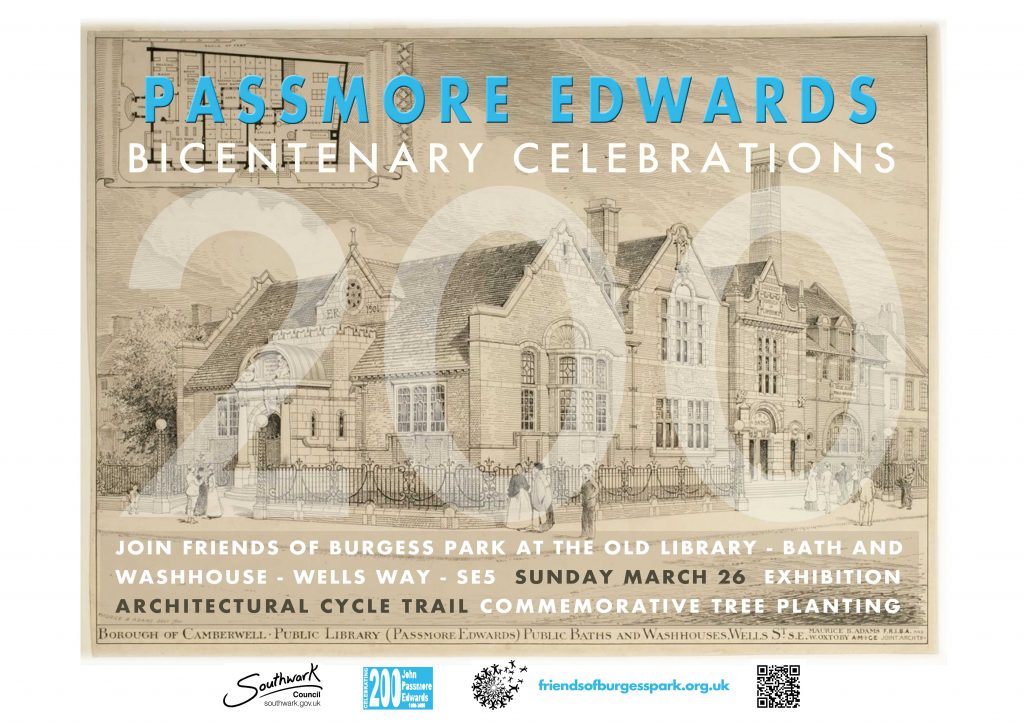

Celebrate the Grade II listed building and it’s benefactor Passmore Edwards.

This year marks the 200th anniversary of Passmore Edwards’ birth on 24th March 1823, and Friends of Burgess Park is joining with others around the UK to celebrate the Passmore Edwards 200 Festival. We’ll be holding a programme of events based at the old library, baths and washhouse on Wells Way on Sunday 26th March. There’s an exhibition about the man and his legacy, children’s activities, a commemorative tree-planting, and a reading by local author Jacqueline Crooks from her new book, refreshments and more.

Bike Tour 2-4pm We’ve also organised a short Bike Tour around three of Passmore Edwards’ south London buildings, guided by a renowned local architect. You can book now for the bike tour 2pm to 4pm on Eventbrite – places are limited to 25, so book early!

Commemorative Tree Planting 4.00- 4.30pm- Across the country Rowan trees are being planted to celebrate the Passmore Edwards bicentenary, join us from 4pm for the tree planting and reading by local author Jacqueline Crooks from her new book Fire Rush, and refreshments.

Exhibition 1-5.30pm – Find out more about Passmore Edwards with an exhibition on loan from the Passmore Edwards legacy. Plus more about the old library bath and washhouse building its history and future role benefitting local people.

Join us on the following dates:

Saturdays – Jan 28th / 11 Feb / 28th Feb and 11 March 11-2pm

All welcome, dress for the weather and woodland work. Booking fee will be reimbursed on attendance. Book here Burgess Park Woodland Maintenance | Eventbrite Booking fee reimbursed on attendance.

Michael Faraday primary school art work for anti-litter banners

Thank you Year 3 pupils (summer 2022) and for helping litterpic. See the banners in Albany Road near Giraffe House and Wells Way near the old library.

FOBP weekly litterpic Every Monday morning 8am to 9am

FOBP provide litterpics, gloves and bags.

Meet at Chumleigh Gardens – in the gardens behind the behind the cafe.

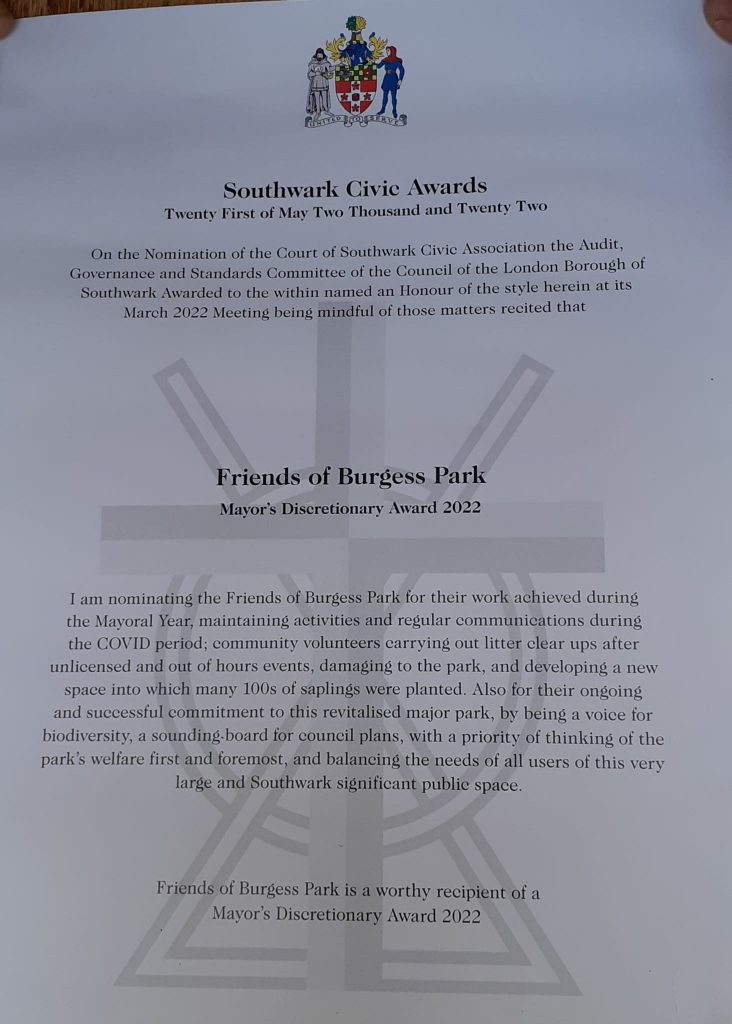

Thank you Southwark Mayor Cllr Barrie Hargrove for the 2022 Discretionary Award for Friends of Burgess Park’s “ongoing & successful commitment … thinking of the park’s welfare first and foremost”. Massive thanks to all our volunteers, past, present, & more importantly, future ones. Join us!

Woodlands wildlife

Highly Commended Our woodlands campaign to protect Southampton Way woodlands against development pressure is highly commended London Urban Forest Award at the London Tree and Woodland Awards 2022. Thanks to all local groups and park users who have supported us.

Highly commended London Urban Forest Award

Blog: Dave Clark

Writing this in January 2022 the focus of birding interest centres around the lake at Burgess Park. Geese, gulls and cormorants increase their numbers at this time of year as they battle to survive the natural elements and human impositions before the high energy sapping spring arrives. Spring, when the days are longer, spring, when optimism fills the air, spring, when not just the lake but the whole park resonates to the natural sounds and movements of birds. Spring is when the lifestage focus shifts from one of survival to breeding; finding territories, finding partners, building nests, laying eggs and having kids … well chicks. With this in mind and the short winter days and long nights providing an opportune mental space for human reflection it’s appropriate to mull over and review the multitude of bird highlights that over the 2021 seasons Burgess provided.

Mediterranean Gull, Josep del Hoyo Macaulay Library

Goldeneye, Dorian Anderson Macaulay Library

Eighty five species were seen across the year by twenty-two observers who provided hundreds of important records of these sightings. There were twelve different long distant spring migrants recorded, either staying for a few days, using the park as a feeding stepping stone or remaining until summer to breed; nine different species of warbler; seven different species of gulls; five different species of birds of prey; two different flycatchers and a partridge in a pear tree … ahem, not really, but a pheasant was indeed seen!

Common Redstart, K. Al Dhaheri Macaulay Library

Spotted Flycatcher, S. Sawant Macaulay Library

However, these numbers are pretty lifeless and unemotive without context. For the true importance of Burgess Park as an avian hotspot and green performer to be understood, we should compare these figures and the interest that they have engendered, to other green spaces. Eighty-five is a tick list that would be expected in ‘wilder’ and more ‘natural’ areas or rural arcadian idylls not in an urban park. Indeed in these traditionally more cosmeticized environments forty to fifty species would be a more likely expectation. Neither are these numbers just birders ticks in a little black book or competitive markers but more importantly denote what can be achieved in urban green spaces at a time when 67% of the UK’s bird species are deemed of conservation concern.

These heartening results do not come by chance. Burgess Park has locational advantages; it is not far from Thames and is characterised by superb vistas which allow birds sightlines of the lake and green areas. But it is the considered management and provision of various habitats which are the key factors in attracting the abundance and diversity of birds: scrub, long grass, wild flower meadows, richly planted gardens and, of course, the important water feature. It is no surprise that many of the rarer species encountered were found in the less sterile environments, environments which we have been institutionalized to think of as rough and unkempt. These pejorative terms mask the positives, we should be thinking rich, diverse and life affirming. ‘Scrub is good’ is the mantra.

For these birds, several of which are long distance migrants, wintering south of the Sahara, to continue to be attracted, these habitats need to be retained and maintained by diligent management and hard work. Management that does not have dominion but understands that nature is at the apex of importance of any green space.

If anyone would like to take part in citizen science by recording bird sightings, the references below should help and if a full annual bird list is required check out this link:

https://ebird.org/hotspot/L7578420

or contact me at: dave@mailbox.co.uk.

Peregrine Falcon, Joshua Stacy Macaulay Library

Resources:

Wild boar, auroch and red deer shaped our ancient woodlands. They grazed on the saplings that sprung up in the clearings caused by falling trees and kept the soil open to the sky. Wildflowers and berries thrived in the sunshine attracting more wildlife. Stone-age hunters found it profitable to hunt where the animals gathered and were able to keep the clearings open using flint axes. Later on, Bronze age people developed the clearings into places to cultivate rough pasture and crops.*

A completely closed canopy is poor in biodiversity as without sunlight, there will be no plants for forage on the woodland floor. The only insects to be found will be those that feed on decaying leaf litter and their predators. The mighty English Oak will not grow here, their seedlings grow best in more open conditions, often under the protection of a Blackberry thicket. ‘The thorn is mother to the Oak.’ When you find an Oak tree in the middle of a wood, it was there first, other trees grew around it.

Throughout the many centuries since, under-woodsmen have harvested the underwood, taking Hazel, Ash and Chestnut to make hurdles, fences, rustic furniture, firewood and charcoal. The standards, Oak and Elm were left to grow on into timber for ship and house building or to become veteran trees. Felling all the underwood may seem like vandalism, but letting the light in regenerates the woodland as the trees quickly re-grow.

The woodland in Burgess Park West is a young Broad Leaf woodland, planted to imitate ancient woodland, but it will be many decades before it develops veteran trees and the complex wildlife that they support. Similarly, with the plants that indicate ancient woodland – Wood anemone, Herb Paris, Twayblade, Purple Orchid, They need deep, moist, leaf mould interlaced with fungal mycelium and soil micro-organisms to grow in.

Sunshine is a vital agent. In a coppiced woodland, sections of the woodland called Coups are cut every 7-12 years in rotation. Under this system, there are always young tree shoots within the reach of grazing animals somewhere in the woods. Other trees and plants are mature enough to produce nuts and berries to feed animals such as dormice. Somewhere in the wood, areas of thick scrub will have sprung up into a site where nightingales can nest. Full exposure to sunlight every decade is enough to sustain bluebells and other woodland flora. In neglected woods, the flora will eventually be shaded out along with all the wildlife it supports.

Coppicing is hard work and under woodsmen a rare breed. In Blean Woods near Canterbury, things are going full circle and European Bison are being re-introduced to look after the woods. Unfortunately, natural habitats are becoming more fragmented by roads and buildings, so it will take a lot of changes to make it possible for native mammals like the hedgehog or the wild boar to return to this bit of London. The plants and trees that have lasted with us into the 21st Century have adapted to our ancient methods of managing the land and to the animals that live on it. But, they can’t keep up with our present rate of change and we run the risk of destroying these beautiful habitats if we don’t understand and fight for what it takes to keep them alive.

Jenny

* See A Natural History of the Hedgerow by John Wright

Ornithologist Dave Clark recommends keeping a record of the birds in the park and on the lake.

This gives us an indication of the natural health of our precious green urban space and allows us to understand the changes that occur seasonally within nature. The winter profile of the lake is one of gulls, cormorants and wintering ducks seeking, believe it or not, a warmer climate from their usual surrounds.

Being proximate to the Thames and easy for birds to see from the air, the wide vistas of the park provide a backdrop that allows avian incomers to assess the attractiveness of the lake, with food and safety being the prime instinctual drivers. This winter the lake has continued to provide a home, stopover and feeding station to the usual suspects alongside less common and in a Greater London context, rare species.

The star of the show was a White-fronted goose which quite happily fed and swam with the resident Greylag geese population, gracing us with its rare presence for around a week. White fronts, check out the white patch above the beak in the above photo, migrate to Britain during the winter to escape the bitterness of lcelandic and Russian winters with this particular bird being one of the rarer subspecies which arrives from faraway Siberia to land habitually on our coastal and estuarine environments, a rarity indeed.

Usually seen, if at all, on the large expansive London reservoirs the Goldeneye is a distinctive wintering duck from Scandinavia. A beautiful male appeared later in January for three days and was probably the same individual that appeared for the same duration on the lake before last year`s lock down.

Other ducks of note that have also been seen are the subtly plumaged Gadwall and a long standing male Pochard in all its orange-red headed glory.

On our playing fields, parkland and ponds there is always a winter build up of gulls, and on any one day during this winter there have been up to two hundred Black-headed gulls swooping and swimming at the lake. We commonly make the mistake of perceiving them as seabirds when in fact they are coastal birds and with the Thames so close the route to the coast is only 20 to 30 miles away. Along with Common gull, Herring gull and Lesser black-backed gull the lake has also attracted, on occasion, Britain’s largest gull the Great black-backed gull, a serious beast standing at 70 centimetres it is twice the size of the usuals and five times the weight!

Finally in our water bird list is the Mediterranean gull which pops in and out of Burgess Park. As suggested by their name they are used to a warmer environment and although still rare the general increase in abundance of this bird in Kent coastal areas is a sign of our changing climate. Very similar to the Black-headed gull the white wing tips and droopy beak help discriminate between the two species.

A heartwarming effect of the lake’s success is the notable increase in the number of observers who are recording sightings on the various social media platforms. I’m sure the coming seasons will add to our birding pleasure, and whether casual or serious in our intent there is no doubt in these strange times that the lake and the park are important for our well being. Keep birding!

Where to record your bird sightings

London database = GIGL = Greenspace Information for Greater London – collects data on flora and fauna – https://www.gigl.org.uk/

BTO = British Trust for Ornithology – strictly birds – https://www.bto.org/

ebird – U.S. app for birds which we are increasingly using for our water and songbird sightings – https://ebird.org/home

Dave Clark

dave@mailbox.co.uk